The Jervais Window, Agher Parish Church, Ireland

Over 50 Years of Excellence in Stained Glass Craft and Conservation

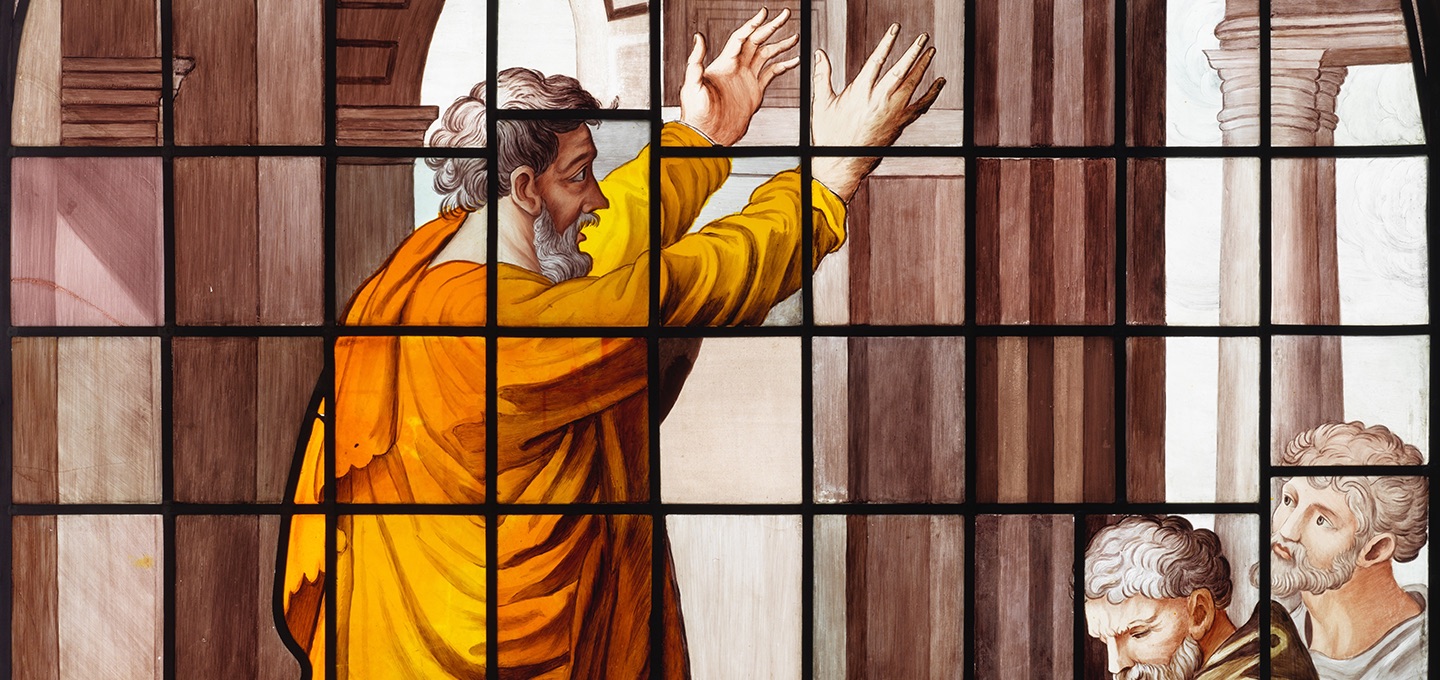

The East Window of Agher Parish Church in County Meath, Ireland, contains an extremely rare example of the work of eighteenth-century glass-painter Thomas Jervais (d.1799). The window depicts St Paul preaching to the Athenian, after Raphael. St Paul, dressed in orange robes, stands within an architectural background, with a trio of figures to his right. The scene is one of a number of cartoons dating to 1515-16 for the scheme of tapestries that adorned the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican (now on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

Jervais was a native of Dublin, and extant records refer to his work in stained glass as early as 1760. By 1777 he had been awarded the prestigious commission to paint the Seven Virtues in stained glass for New College Oxford's chapel, to the designs of renowned artist Sir Joshua Reynolds. The Agher window has been attributed to the year 1770; the same year Jervais moved his studio to London. The window was originally made for Dangan Castle, near Summerhill, the large private home of the Wellesley family. The house underwent several phases of re-building and restoration in the eighteenth-century, and in 1793, after the sale of the house and lands to Captain Thomas Burrowes, two new wings were added. This included a chapel, where the window may have been re-located to. The house was gutted by fire in 1809, but the window survived unscathed and was moved to nearby Agher Parish Church. The window stands as one of the oldest stained glass windows in situ in Ireland, and appears to be the only surviving Jervais window in his native Ireland.

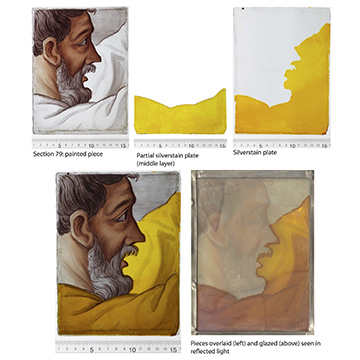

The glass in the window varies between 4mm and 1mm, and cold-paint has been added after the enamels have been fired, seemingly done at or soon after the window's manufacture. Most extraordinary is the different applications of silver stain - applied in some places through the use of sheets of silver leaf - and the use of layers of glass; sometimes painted or stained. These had the effect of enhancing the richness of colour.

Evidence of Jervais's experimental or novice approach can be found in his application of paint. The edges of the glass, hidden beneath the lead calmes, were left unpainted, making it possible to speculate that Jervais painted the glass pieces while they were part of a leaded matrix. It may be that he chose to paint the glass pieces vertically, as if on an easel, before then fully or partially dismantling this leaded framework, by making incisions in the lead and sliding the glass pieces out in order to fire the glass paint, before re-leading it again. While this would have been a non-standard and labour intensive method of working, it would have ensured that key linear elements of the composition aligned. Jervais's cold-painting of areas of the glass, and his extensive use of painted plates, indicate his attempts at further modifying the appearance of the design, perhaps indicating that he was occasionally dissatisfied with the way in which some of his pieces were firing in the kiln. At times, several layers of silver-stained glass have been leaded together to create the desired depth and tone of colour. The different plating systems physically gives the window a highly textured and varied surface appearance, as well as a visual depth and range of colour. His use of selectively stained plates in areas around the face, shoulders, arms and hands of St Paul may indicate a reluctance to apply silver stain directly to important areas of the design; he could not risk the stain failing and potentially ruining these pieces, preferring rather to build the colour with separate pieces of glass. Sheets of silver leaf have also been used at times to colour the glass; a noteworthy and pioneering technique.

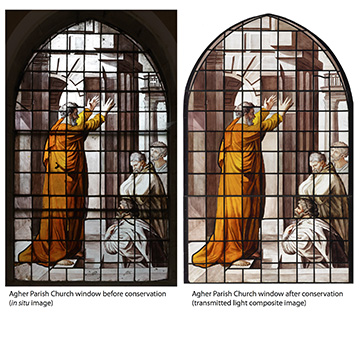

At the behest of the Irish Georgian Society, the window was examined in 2014 by the York Glaziers Trust, and found to be in a perilous structural and environmental condition, with severely deteriorated leads and extensive microbial growths. The Trust recommended that the window be removed for conservation and reinstated with internally ventilated protective glazing. Fortunately, this work was able to proceed in 2016 after an export licence was granted by the National Gallery of Ireland in order to permit the removal of the window to the York Glaziers Trust's studios. Challenges during conservation arose in the cleaning of some sections - several areas had an unexpected layer of (likely original) cold-paint, necessitating that every piece of glass was painstakingly cleaned by use of high-definition binocular microscopes. The re-leaded window was returned to the church with a new bespoke frame.

For a fuller version of this article, see L. Tempest, N. Georgi, and N. Teed, '‘Thomas Jervais and the East Window of Agher Parish Church, County Meath, Ireland’, in S. Brown, C. Loisel et al. (eds), Stained Glass: Art at the Surface – Creation, Recognition and Conservation, 10th Forum for the Conservation and Technology of Stained Glass, York, 2018, pp. 202-13.

Project Value and Funding:

Grants were awarded by the Irish Georgian Society (Ireland, London and Chicago Chapters), the Primrose Trust, the Gaeltacht's Built Heritage Investment Scheme, the Select Vestry of Rathmoylan Union of Parishes, and by funds from the current Duke of Wellington.

Selected Bibliography:

S. Baylis, 'St George's Chapel, the Eighteenth-Century Windows - and Where are they now?', in S. Brown (ed.), A History of the Stained Glass of St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, Windsor, 2005, pp. 79-107

W. G. Strickland, 'Thomas Jervais', A Dictionary of Irish Artists, 2 vols, Dublin, 1913

C. Woodforde, The Stained Glass of New College, Oxford, Oxford, 1951

M. Wynne, 'Irish Stained and Painted Glass of the Eighteenth Century', in P. Moore (ed.), Crown in Glory: A Celebration of Craftsmanship, Norwich, 1982, pp. 58-68

Get In Touch

If you would like more information on our conservation services please get in touch.

Contact UsContact Us

The York Glaziers Trust, 6 Deangate, York, YO1 7JB